I’ve decided to take advantage of a slight lull in the work schedule and…gasp!…take a day off. But I leave you in the capable, if slightly gore-coated, hands of E.C. Ambrose, who has been delving into a particularly fascinating bit of history for their recent “Dark Apostle” novels…

Medical Excellence in the Middle Ages

E.C. Ambrose

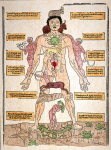

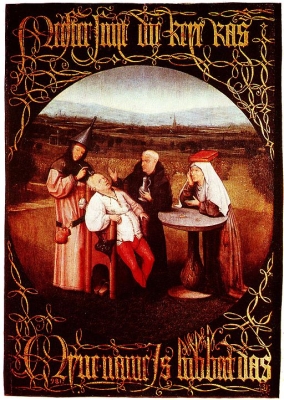

You weren’t expecting that headline, were you?  When people imagine Medieval surgery, most picture a bloody saw in the grip of a man educated by a book written a millennium before by Galen, who drew his ideas about anatomy from dissecting pigs. With the recent interest in the use of larvae to clean gangrenous wounds and the efficacy of leeches in the reattachment of severed limbs, it’s time to take a closer look early surgical practice. While the surgeons of the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries had limited science, they had a specialized knowledge of common problems faced by their ​primary clientele, the warrior classes of the Middle Ages.

Medieval surgeons achieved their level of practice either through a formal education in one of the universities of the time (Paris, Saleron, Bologna, Prague), or by apprenticeship with a practicing surgeon—just like the interns and residents of today. This gave them real-world knowledge they could apply to their own patients.

The medieval surgeon had an awareness of the problems likely to be faced by his clientele, in the same way that today’s orthopedists might look for injuries associated with specific sports or occupations. One common malady was anal fistula, a very painful condition resulting from spending too much time in the saddle, often suffered by the knightly classes, but also developed by lesser men as a result of damp conditions or dietary problems.

The operation to cure the fistula was notoriously dangerous. However, the English surgeon, John of Arderne (c. 1307- 1380), specialized in this treatment, developing tools and techniques, and writing a manual to share his practice with others. Arderne goes so far as to include a number of case studies, claiming that patients he treated in the described manner were able to ride again a mere forty days later. While it’s hard to judge such claims today, it’s clear from the number of contemporary references to this work that Arderne was considered a leading surgeon among his peers.

One operation occupies a special place of horror in the modern conception: that of trepanation. Trepanation is the technique of drilling into the patient’s skull to relieve pressure on the brain, usually resulting from a compressed skull fracture. In the late Medieval period, given the prevalence of combat in general, and mounted combat in particular, skull fracture was not uncommon, and the surgeons of the time developed careful practices to treat it.

For many years, the instruments required were the same a carpenter might use, a hand drill for piercing the skull, sometimes in multiple areas with the skull between then scraped away carefully with a rasp, or a smaller probe inserted into the holes to elevate the depressed bone in between. An adept practitioner could complete the operation in about half an hour, and studies suggest that up to 90% of patients in the 1400’s survived the operation.

Medieval surgeons also had specialized tools and techniques for handling opthamology, and surgery of the eye was particularly advanced in the Muslim world. Cataracts clouded the vision and could severely limit the quality of life of the medieval patient, but a skilled surgeon could use a scalpel and delicate approach to “couch” the cataract and significantly improve vision. The eye would be washed with salt water and treated with oil of roses and egg whites to prevent infection. Patients were advised to lie on their backs for several days afterward.

One of the truisms of historical fiction is that history is like a foreign country—they did things differently back then. However, my research into medieval surgery suggests that, just like now, medical practitioners were motivated to improve their tools and techniques, to learn from one another, and to strive to create better outcomes for their patients. A surgeon at the time might be greatly rewarded for his success—granted royal or papal patronage, given estates or wealth. Given that one side-effect of a failed surgery was often the slaying of the surgeon, they had an added incentive for excellence.

Elisha Mancer, book four in the Dark Apostle series of fantasy novels about medieval surgery, launches this month! For sample chapters, historical research and some nifty extras, like a scroll- over image describing the medical tools on the cover of Elisha Barber, visit The Dark Apostle.

over image describing the medical tools on the cover of Elisha Barber, visit The Dark Apostle.

E. C. Ambrose blogs about the intersections between fantasy and history.

Buy Links for volume one, Elisha Barber: